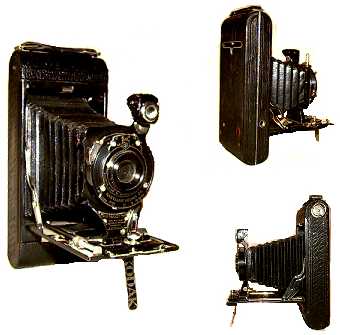

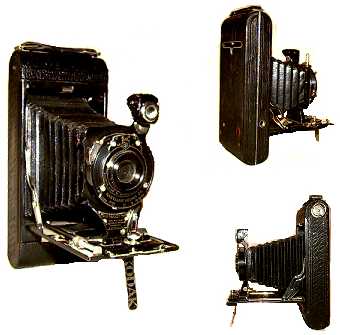

Kodak 1a Pocket Folder with Stylus

Photo thanks to Chip Middleton [email protected]

Related Links:

LF

Wide Angle Lenses (QTL's site)

Kodak #3A Manual (courtesy of Richard Urmonas) [5/2002]

| Shifting Panoramic Rollfilm Camera Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Postcard Panoramic Camera |

| Format: | 6x12+cm (2 1/4" x 5 1/2") |

| Panoramic Ratio: | 2:1 to 2.4:1 (varys with model#) |

| Film Type: | 120 rollfilm (optional 220; 70mm) |

| Special Features: | +/- 13mm shifts |

| Shifting Mechanism: | film shifting

(set when film loaded) Lens shifting (vary lens position on some models#) |

| Weight: | under 3 pounds |

| Size: | compact folding folder

style fits in jacket coat pocket |

| Camera Modifications: | none required |

| Lens Modifications: | none required |

| Rollfilm Modifications: | simple $2 velcro'd dowel adapter |

| Std. Lens Angle of View: | circa 46-54 degrees

(varies by model#) |

| Standard Lens: | equiv. to 50mm on 35mm SLR |

| Panoramic Camera Cost: | $25-40 US |

| Camera Model: | Kodak #3A Postcard (#122 film) Camera |

| Wide Angle Lens Option: | equiv. to 30mm

on 35mm SLR (with 0.6X adapter) |

| wide angle option cost: | $20-25

US (for 0.6X adapter) |

| Ultrawide Lens Option: | equiv. to 21mm

on 35mm SLR (with 0.42X adapter) |

| ultrawide angle option cost: | $25-50

US (for 0.42X adapter) |

| Non-Shifting 6x12cm Panoramic Camera | |

| Camera Name: | Compact Panoramic Camera |

| Panoramic Ratio: | 2:1 |

| Film Type: | 120 rollfilm (optional 220) |

| Format: | 6x12cm (2 1/4" x 4 1/4") |

| Shifting Range: | minimal to none |

| Panoramic Camera cost: | $25-40 |

| Camera Model: | Kodak #1A Autographic (#116 film) Camera |

| Recommended Options: | bubble levels

($5 up) wire frame finder ($5 US) |

These cameras are already setup for panoramic photography, with panoramic

ratios of 2.4 to 1 (#122) or 2 to 1 (#116). The #122 rollfilm format was

roughly 3 1/4" x 5 1/2", permitting direct contact prints the size of

postcards. Using 120 rollfilm, you get from a 6x12cm up to a 6x14cm (55mm

x 130+mm) image size.

Although the 5 1/2" format axis suggests a 14cm sized opening, my own

Kodak #3A model C panoramic camera features a film gate more like 12cm in

length, possibly foreshortened to provide for the autographic feature.

This autographic feature is a small flap that flips up, permitting you to

write notes on the film (which had a black surface for recording). On some

other camera models, you may get the full 14cm (5 1/2") width, which would

be a plus. While the actual format on film is 5.5cm x 12cm, the printing

ratio is expressed as 6cm x 13cm (about 9% longer and wider due to

rounding off 5.5cm as 6cm). See MF Formats

in the MF-FAQ for other actual film size versus printing ratio

values.

I call this camera the Postcard Panoramic Camera.

The #116 cameras produce 2 1/2" x 4 1/4" sized images. Using 120 rollfilm,

you get 6x12cm format images. Since it is smaller, I call this the compact

panoramic camera.

You don't have to do anything to modify either

the camera body or lens to make them into panoramic cameras.

We just have to come up with a simple way to use 120

rollfilm in these cameras to put them back to use as panoramic

cameras.

A simple wooden dowel based adapter piece is all it takes to convert the

camera to 120 rollfilm. This idea and solution was published in Shutterbug in April, 1990 issue (page

147) by Judge Marty Magid. If you would prefer to purchase ready-made

adapters, see adapter information

(section 7) for his address. You can also follow our instructions there

to make your own simple adapters, using a dowel rod.

You could recycle the 120 film spool guides from an older 120 rollfilm

camera such as a low cost Kodak brownie ($5 in garage sales). Now file,

epoxy, and carefully center mount these scavanged 120 film guides into the

older camera. This approach would work especially well with the compact

panoramic camera design, where there is only 1/4" vertical slack in the

film channel. You could also use your scavanged 120 film guides on the

adapter ends of the postcard panoramic camera. In both cases, the film

winding and rewinding mechanics end up working as before, just with 120

rollfilm instead of the wider #116 or #122 rollfilms respectively.

You can simply put a 120 rollfilm in the camera and mate to a

matching 120 film empty spool engaged by the film winding knob on the

Kodak #3A camera. Naturally, the 120 film spools are about an inch too

short to engage the far end of the #122 film spool round guides. You need

some sort of spacer (fat dowel end?) to keep the 120 rollfilm spools from

being loose in the longer #122 film spool channel.

This minimal approach also "costs" a bit of the 120 film width, which runs

along the top edge of the camera. But this may provide a flatter film run

due to the support along this same edge (try this trick if you have

film flatness concerns). However, I should note that on my Kodak #3A,

there is a thin metal rod under which the rollfilm goes before going

across the open film gate, then under another similar rod at the other end

to the take-up spool. This film winding process is a useful alternative to

precise pressure plates.

You can

either put in some sort of spacer or a spring (e.g., fat round dowel an

inch or so long cut to fit) that permits rotation, or

build a slightly more complex film adapter as suggested below. Another

option is to use an existing #122 empty film spool as the take-up spool

for a standard 120 rollfilm. The hole in the #122 film spool is centered,

and easily takes up the film from the 120 rollfilm. Naturally, in this

case you would want some sort of pair of adapters on either side of the

120 rollfilm spool to keep it centered. You would also need to do home

processing from the #122 spool loaded with 120 rollfilm, or make

arrangements with the commercial processors. You could also simply use a

film changing

bag to spool the 120 rollfilm off the #122 film spool and onto an

empty 120 film spool for regular processing.

On some cameras models (e.g., my Kodak #3A model C), the rear back

removes entirely to permit mounting a ground glass and sheet film adapter.

This feature can be handy to check lens focusing (including centering the

lens vertically). The Kodak #3A has a lens mount that permits moving the

lens up and down (vertical shift) which can be used in addition to the

film shifting techniques described below. Removing the back and checking

with ground glass (no film inside, obviously) makes it easy to see what

you should get on film.

One factor making it easy to create removable adapters is the ability to

use

empty 120 rollfilm adapters, since they neatly fit the camera's rotating

#122 film guides (as noted above). For example, you can cut a standard

empty 120 rollfilm spool so only one inch remains from each end. Use a

dremel drill and grinding bit to grind away the precise amount you

need. Use some plumbing epoxy (very solid) to solidly epoxy a small metal

screw to the adapter. The round part of the screw should fit into the

round holes of the 120 rollfilm spool (with film). A pair of nuts on the

screw can be moved to precisely position the length of the entire 120

rollfilm plus adapter combination so it exactly fits the #122 rollfilm

channel.

The full 120 rollfilm film supply spool should be able to turn freely on

the two round supply side film guides on the Kodak #3A camera.

Incidentally, these guides can be pulled out to make them flush with the

base of the camera, then released to mate with the properly positioned

film spool which fits flush in the camera. So you can make a solid 120

rollfilm and adapter combination that matches the longer #122 rollfilm

length, yet still get it into the camera easily using this trick.

On the other side of the film channel, the empty 120 rollfilm takeup spool

and adapter(s) should be positioned to an identical vertical position (to

prevent film buckling from moving sideways across the film channel). You

may want to use a flat blade (e.g., from a

broken screwdriver) epoxied to the end of the 120 rollfilm adapter which

mates with the flat-bladed film winding guide. This blade should obviously

fit the 1/2" or so width of the 120 film spool flat channel, and not be

too long or too short to prevent engaging easily. Remember that it is only

this one flat blade engaging the film spool that provides the turning and

motion of the film in the camera. The other round film guide

("bumps") just let the film spools turn easily in proper position.

Before you dismiss this glass plate idea as too problematic, consider the

older Hasselblad polaroid backs. Unfortunately for Hasselblad, the standard

Polaroid mechanism couldn't be mounted at the desired film plane position. So

a thick uncoated glass plate was used to channel the light to the recessed

polaroid film position. The glass plate was also a flat surface too. Zillions

of proof photos, and quite a few Polaroid negatives (from positive/negative

films like P/N 655..) have been shot in such older Polaroid glass plate backs.

If it is good enough for Hasselblad users, it should be good enough for us too!

Simply get a piece of thin glass from a glass

supply house (glazier) cut to fit snugly in your camera. Be sure to get

them to polish at least the two edges over which the film will move to

eliminate scratching of the film. Given the small size of glass needed

(8cm x 12cm+), costs are often surprisingly low (under $10 US). Even better,

some glass sources (see notes below) can provide thin glass plates which are

coated to reduce reflections for a small extra cost.

The glass is mounted under the film, between the film and the camera lens.

The size of glass is such that it can fit on the old, larger film channel.

You want the glass to stay in place. Some household cement can keep it

in place with a few dabs on top of the glass and onto the camera body. But

don't put the cement under the glass, as you want it to be held flatly

against the camera back and old film channel. Any cement under the glass

would produce non-flat results depending on varying thickness, so don't

get any under there!

The glass acts as if it were a clear filter behind the lens. Lots of low

and mid-cost camera filters are made from plate glass. So don't worry that

your image will be visibly effected. Typically, filters behind a lens

cause a small focus shift, roughly equal to a third the thickness of the

glass itself. You therefore want relatively thin glass, which also has

fewer unrelieved stresses and better optical properties. But you don't

want the glass to be too thin, as it could break too easily (e.g., below

5mm thick?).

With the glass glued in place, the film cannot now bulge in the center as

it might have before without such a flat support. A bit of padding on the

back of the camera can help force the film into contact with the flat

glass plate. If you have some camera mirror foam strips of 5mm or so

thickness (e.g., from Fargo Enterprises) you may find these self-adhesive

pads work well here too. But you can use whatever padding you want as long

as it is not too thick and flexible. The 120 rollfilm has a paper backing

preventing you from scratching the rear of the film. While it may be

obvious only after you make such a modification (ahem), it helps to

remember to cut or leave an opening so you can still see the film

positioning numbers on the paper rollfilm back through the ruby (red)

window!

You don't want too much pressure, so you don't get scratches when you

advance the film. You may find that the camera back is flexible enough

that simply pressing in with fingers or thumbs on the rear of the camera

back, while shooting handheld or on a tripod, will supply enough force to

flatten out the film against the glass and under the foam back or other

padding. Releasing that pressure while you advance the film

prevents scratches. Simple!

Naturally, you need to check the film position and focusing with the added

flat glass sheet in place. Again, this is easily done with a small sheet

of ground glass (also available cheaply from the glass supply house) and a

loupe or other magnifier. The ground glass goes so the ground glass

surface is where the film would be when pressed down on the back of the

glass plate (e.g., flipped so it is closer to the camera lens, not the

viewer's eye).

You may have to adjust the position of the lens slightly to achieve

optimal infinity focus (possibly with unscrewing the lens slightly or

adding a shim under the mount). Moreoften, you can simply adjust the

focusing positions by sliding the lens on its existing focusing mount.

Simply relabel the correct new positions for different distances on a

paper scale sheet next to the old focusing distance markings. When done,

cover with scotch tape or other waterproof covering. Since most panoramics

are not used for closeups, but chiefly at infinity focus, the infinity

focus point is the really critical point you need to establish.

If this plate glass idea sounds crazy, it is actually an old trick. The

Rolleiflex TLRs had an accessory glass plate that could be used to improve

film flatness. Thin glass plates have been used in large format enlargers

to minimize film bulging during enlarging for years. Problems with

flatness in some medium format cameras were cured using similar flat

glass plates between the film and the lens (see Hans Maersk-Muller's

How to Flatten Your Film for Sharper Pictures in Modern

Photography of April 1970 (pp.78-9, 120).

I don't understand why this film flattening solution isn't wider known and

used, but perhaps this page will help spread the word? The alternative

panoramic homebrew cameras often use very expensive 6x12cm and 6x17cm

rollfilm backs, or modify and build one from scratch or torpedo cameras. By comparison, this simple glass

plate technique costs very little, is easy to do, and requires no

precision tools or machining. You also don't have to build anything more

complex than a rollfilm adapter to use the rest of the older folder

cameras mechanics and mountings either. You are still way ahead even if

you elect to put in a wider lens (such as the low cost 90mm Angulon which

can cover 150mm on rollfilm without movements). For most folks,

this postcard panoramic camera will serve as an easy project and low cost

introduction to medium format panoramic photography.

On most of these older folder lenses, the front and rear elements will

simply unscrew. You probably don't need to do anything more than clean the

inner (and outer) lens surfaces. Don't try to disassemble the lens

elements beyond the simple unscrewed front and back element level. A

pencil mark or two will help ensure you get them back in place in the

right alignment. Once cleaned (using Kodak lens paper to wet and dry), the

lenses may well sparkle like new!

While you have hopefully tested your postcard camera before buying to

ensure the lens diaphragm and shutter speeds worked properly, you may find

some of Mr. Romney's repair books and

related resources (possibly in your local

library?) to be handy. You might get stuck with an Ebay non-working "minty bargain" that doesn't work as

advertised. As long as the shutter speeds are consistent, you

can probably adjust your film speed as used on a handheld meter to produce

usable exposures. It is much easier to adjust the exposure than to

clean up and repair an older leaf shutter mechanism the first time!

Film shifting produces essentially the same result as lens shifting. You

are able to control certain optical distortions such as converging lines

in your photographs. If you are familiar with the benefits of shift lenses, then you will

realize what a great advantage a shift camera has over other fixed and

non-shifting models.

With a shift lens, we hold the film in place in a rigid film channel and

move or shift the lens up or down vertically. Moving the lens up or down

moves the part of the image formed by the lens up or down on the

film. As you move the lens up, the top part of an image will

be shifted down onto the film. Usually, shifting a lens up is a great way

to keep the camera level while eliminating converging vertical lines, but

still get the top of a building or other subject into the image.

Film shifting is the other way to do it. With film shifting, you leave the

lens in place, and shift the film up and down in the film channel. If you

think of the lens' circle of coverage, you can either leave the film fixed

in place and shift the lens up or down, or you can leave the lens in place

and shift the film behind it up or down. Either way, you can move the film

relative to the lens circle of coverage to place the film where you want

it in that lens circle of coverage circular image (at least up and

down-wise). Make sense?

The big advantage of film shifting is you don't need a custom

kilo-buck lens specially designed with shift mechanisms to move the lens

up and down. You just need a camera with a wide film channel in which you

can move the film up and down, and a lens that can cover this full range

of film shifting movements.

If it is easier to shift the film than the lens, then why doesn't anybody

do

it? The short answer here is nobody wants a bigger heavier camera, so the

cameras are designed to precisely fit the selected rollfilm they use. If

you are going to build a rollfilm camera with a bigger size and film

channel and lens coverage, you might as well use a rollfilm that fits that

bigger size channel. Simply crop out a panoramic format, if that's what

you want. Or crop and print the full sized print, such as the 3 1/4" x 5

1/2" postcard sized images produced by our Kodak #3A postcard

cameras.

But as this shifting panoramic camera demonstrates, a one inch wider film

channel and one inch bigger camera is a very small price to pay for the

benefits of the resulting +/- 13mm of shift available!

How do you get this range of shifting capabilities in practice? The short

answer is that you vary the size of the dowel used to mount your 120

rollfilm in the #122 camera. That's it - it is really that simple!

If you use a minimal dowel size, the film will be at the top of the 3

1/4" film channel. This position is equivalent to a -13mm shift. Since the

lens inverts or flips the image, the bottom of the image is at the top of

the camera. The very bottom of the image will be on the film now. The

result is the same as shifting the lens -13mm downward and keeping the

film fixed in place in a conventional shift lens camera.

At the other end of the film spool, you may need a corresponding bottom

adapter so it fills the rest of the film channel and the film spool

doesn't fall out of place. These end adapters can be velcro'd onto the

bottom of the film spool, as described at our film adapter pages (see item #7). At the maximum

+13mm film shift position, you don't need a bottom adapter piece at all,

since the film is flush with the bottom of the camera. At shifts from

circa +8mm to +13mm, you can simply use a dime, nickel or a few coins to

take up that space at the bottom of the film channel and rotate freely.

That is handy, as it would be inconvenient to build a small enough dowel

adapter to fit.

You can probably guess that you will need one set of these 120 film

adapters for the take up spool, and one set for the film supply spool on

each side of the camera. But since they only cost a dollar or two to make,

these film adapters aren't expensive or hard to make.

What if you add 13mm to the length of the dowel adapter (e.g., by turning

a bolt into a nut a given number of turns). Now you have centered the 120

rollfilm in the center of the #122 rollfilm channel. The 120 rollfilm will

have 13mm of space above it, and 13mm of space below it. The 2 1/4" width

of the rollfilm and the 1" width of the spaces (13mm + 13mm ~= 1 inch) add

up to the 3 1/4" width of the #122 rollfilm designed for use in the #3A

postcard camera.

Finally, what if you add one inch or 26mm of length to the dowel

adapter? Now you have shifted the film so it is in the bottom of the

camera. Since the lens inverts the image, the top of the building or other

object will now be on the film.

Here is the critical point. With that extra 26mm of extension on your

dowel film adapter, you have pushed or shifted the film +13mm from its

central position behind the lens. This film shifting is equivalent in its

effect to moving the lens the same +13mm in an upward shift. This position

is very desirable, since it can cure many problems with converging

verticals in architectural photography.

How about lens coverage issues? You have plenty of lens coverage,

since the lens isn't shifted at all. The lens in these cameras were

designed to cover the full 3 1/4" x 5 1/2" image without vignetting.

What we are doing is similar to putting 35mm rollfilm in a Bronica 6x6cm

SQAI rollfilm back. We are using only a part of the available postcard

sized coverage (2 1/4" out of 3 1/4"). But because we can shift the film

around in the 3 1/4" sized channel, we get to pick which part of that

postcard area is used. By comparison, all of the medium format panoramic

backs (such as the Bronica 35mm or Mamiya 7 rangefinder 35mm option)

provide only for fixed film positions in the center of the

back. Similarly, when you mount a rollfilm back in a view camera, it

is fixed firmly in place (usually centered). You have to use the inherent

shifting movements of the view camera lenses on their standards if you

want shift lens effects.

My film shifting system lets you shift the film around. The 120 rollfilm

doesn't have to be centered in the larger #122 film channel. You can move

it up and down, and effectively get shift effects by doing so.

I am aware of one panoramic camera that has a fixed film channel but a

permanently shifted lens. The Linhof 612 has a built-in shift (+8mm) which

is permanently in place. The designers decided to compromise, assuming you

would so often want or need a +8mm shift that you would want it

permanently built-into the camera. Leif Ericksenn in his medium format

guidebook notes that this approach makes the camera hard to use with

vertical shots. When you don't need or don't want the +8mm shift, you

can't get rid of it either. That's one reason the custom variable lens

shift (Silvestri..) and non-shifted 6x17cm panoramic cameras are more

popular.

While you can setup any desired film shift within the +13mm to -13mm

range, there is one obvious issue with this approach. You have to set the

film shift when you load the camera. You do this by selecting a film

adapter length to put the film where you want it (center, top, bottom..).

But once you close the camera, you can't change the film shift

setting.

You set the desired film shift by either choosing the appropriate film

adapter dowel length (minimal to 26mm), or perhaps fine-tune the setting

by turning a nut in a bolt in some modified deluxe designs. In practice,

you are probably going to want only the centered, +13mm maximum plus

shift, and one or two intermediate shifts (+8mm). So you will only need

two or three low cost dowel adapter pairs to be able to exploit a range

of film

shifting effects.

If this limitation of one film shift setting per roll of film seems

limiting, remember the unchangeable fixed +8mm shift on the Linhof 612.

Moreover, on a 6x14cm camera, you are only going to be taking 4 shots per

roll of 120 rollfilm. We are using the easy peep-window film paper back

numbers on 120 rollfilm for alignment and counting exposures.

If you bracket your shot and shoot a "second", you have used up the 120

rollfilm's four shots right there. Bracketing takes at least three shots,

including one above and one below the ideal exposure (from a handheld

meter), just

in case. A "second" is a second exposure at what you think will be the

ideal exposure. With a "second", you have a backup shot that is the same

quality as the original, since it is a "second" original. A duplicate

6x14cm image is going to be hard to get, expensive, and inevitably will

lose some quality since it is a copy of the original and not a "second"

original. Even if you don't bracket, you are only going to be getting a

few scenes on any one roll of 120 film when you are shooting 6x14cm

images!

In short, I don't see this limitation as particularly alarming. If you are

going to shoot landscapes or vertical shots, without converging verticals

(like trees), then

put in the adapter to center the film in the camera film channel. If you

are shooting in a town, where +8mm film shifts would be handy, just use

the right film adapter to get that desired shift. For times when you have

tall buildings and you need all the shift you can get, set the full +13mm

shift adapter in place. If you really must change from the film shift you

have set, just finish the roll in place and rewind it. Reload with new

film, setting the needed amount of film shift. Simple, even if it might

cost you a few shots now and again. Film is cheap, at least compared to

the cost of other shift lens panoramics.

While this lens centering control may offer

only a limited range of vertical shifting, it does offer some

range of movement (circa +/- 10 mm). That might be enough, with film

shifting to provide some needed perspective controls. So while you may be

limited with "film shifting" to an initial amount of shift, you may be

able to add or subtract from this "film shift" factor by some range (such

as 8 to 10mm or more?) thanks to the lens centering and shifting feature.

There is also a control for focusing by moving the lens horizontally

against a marked focusing scale on the baseboard lens mount. What

makes this factor interesting is the ease with which a shorter and

wider coverage angle lens might be mounted and focused using such

existing hardware. Moreover, you could give up the compact folding

option to adapt a very wide angle prime lens (e.g., 90mm f/8

angulon).

You may want to consider buying the ends of ten inch wide printing paper

(per a tip posting). This paper is on spools,

which are exposed, cut, and processed to make ten inch wide by however

long prints you want (such as 8x10" or 10"x10" wedding photos). In this

case, you might make a full 10" wide image by however long your format and

cropping permits. Starting with a 55mm wide image on 120 rollfilm, you can

only enlarge by a factor of 4.5X to make the ten inch wide image. With our

6x14cm camera, the actual film width (see table) is 130+mm. Enlarging this

dimension by 4.5X gives us a 23 inch long or nearly two foot long

image. Each panoramic will have the equivalent area (and cost) of

about three 8x10" prints.

Naturally, you can crop out different panoramic images and ratios by

cropping instead of printing the full 55mm wide image. Cropping our 55mm

wide film and using only 43mm of it will result in shifting the panoramic

ratio to 3:1 (for 130mm long film width in our 6x14cm camera). So

you may end up using somewhat longer prints by cropping the

height, and larger enlargement ratios. But unless you have a

5x7" enlarger on a special mounting, it may be hard to get the

longer length panoramic prints exposed. After that, you may also

need special developing tubes or use dip processing in a darkroom

to develop the panoramic prints.

| Film Format | X (mm) | Y (mm) | Pan Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6x4.5 | 41.5 | 55 | 1.35:1 |

| 6x6 | 55 | 55 | 1.000 |

| 6x7 | 55 | 69.8 | 1.25:1 |

| 6x8 | 55 | 75 | 1.34:1 |

| 6x9 | 55 | 82-84 | 1.5:1 |

| 6x10 | 55 | 92 | 1.67:1 |

| 6x12 | 55 | 112 | 2:1 |

| 6x14 | 55 | 130 | 2.36:1 |

| 6x17 | 55 | 156 | 2.84:1 |

| 35mm | 24 | 36 | 1.5:1 |

If you don't have a 5x7" enlarger, your local pro photo lab should have

one and be able to provide similar services. They will probably be setup

to make prints with the longer 10" wide film paper rolls too. But since

you will be asking for a custom service, you may get hit up for extra

costs over the cost of the equivalent printing paper width of three

8x10" prints.

To get wider prints is harder, since you have to cut or crop larger pieces

of photo paper (e.g., 30x40"). With a 30"x40" paper, you can enlarge to

40" long by a 7.8X factor, resulting in a 17 1/2" by 40" panoramic. A more

economical approach is to split the 30x40" paper in half, using a 6.9X

enlargement. You get a 15" by 35.3" print, which can be trimmed off the

edges with less paper loss while cutting your costs in half.

Projecting panoramic prints is also a "deja-vu all over

again" experience. You will find lantern slide projectors which can be

adapted to handle various panoramic slide film shots for projection. See

our medium format slide projector

pages for notes and tips. You can also modify overhead projectors and

other items such as enlargers to serve as makeshift projectors. The effect

of a panoramic slide projected on the wall makes up for all the hassles

and minor cost that this approach involves, and then some.

Quite frankly, those panoramic medium format images look rather nice just

sitting on a light table. You may also find some commercial slide holders

for panoramic format images available, or you can use low cost medium

format clear sleeves as many photo processors do.

| What Size Format for Panoramics? |

|---|

|

Is it worthwhile spending the major $$$ to get into 6x17cm panoramics? The

answer is obviously yes if you need contact prints from those 2.83:1 ratio

images. They do have a lot of impact! But it is a different story if you

are enlarging! You can crop a 6x12cm image and enlarge about 42% to create

a 2.83:1 format as used in the 6x17cm panoramic cameras. But the weight,

size, and cost of a 6x17cm camera is much larger than that of the

6x12cm camera format.

With panoramics, we rarely push the grain or

resolution limits of the film. We only need a 4X enlargement to go from a

6x17cm negative to a 10x30" panoramic (cf. 4x6" print on 35mm SLR is also

4X). Cropping the 6x12cm negative to produce a similar (2.83:1) format is

under 6X enlargment factor (cf. 6x9" print in 35mm). We will probably

notice minimal differences in enlargement quality below 8X (cf. 8x10" on

35mm). If the intended print is not 10x30" but a bookcover (even both

front and back) or magazine page (even both pages), the enlargment will be

even less critical.

On the other hand, a 6x12cm is much smaller and lighter, uses less film

per shot (yielding more shots per roll), and much cheaper and easier to

build. It is much, much easier to build a truly flat 6x12cm back than a

truly flat 6x17cm back. It is much easier and cheaper to find a 6x12cm

rollfilm back than a 6x17cm back. Lenses for 4x5" that cover 6x12cm as

wide angles are much cheaper and easier to find than 5x7" wide angle

lenses that cover 6x17cm.

When you check out the actual coverage of the 105mm lens that covers the

Fuji G617 6x17cm (5x7"), you have 73 degrees of coverage (cf. 24mm lens on

35mm SLR horizontally). Our superwide 0.42x adapter yields a 21mm

equivalent (on 35mm SLR) which is wider than the panoramic you would get

on the Fuji G617's 105mm lens! Granted, the fuji lens will be much sharper

and more contrasty, but it won't cover more. You can find 4x5" 75mm or

90mm lenses which will have similar coverage on 6x12cm, but for far less

money and less weight and bulk too.

So don't bother to "lust" after that 6x17cm camera - a 6x12cm will be much

smaller, lighter, cost less per shot, and be easier to make or adapt. And

because of the small difference in enlargements in most panoramic print

end-products (magazines, books, wall prints), you probably wouldn't be

able to tell the difference between the 6x17cm and 6x12cm prints - except

on your wallet and back-strain! ;-)

|

You might not like the standard lens format, which is similar to most

normal lenses on cameras (e.g., 50mm on 35mm SLR). These postcard lenses

are also slow, often at f/6.3 to f/7.7 at best, but we will rarely be

using them except on a tripod anyway. While focal lengths vary

widely with different models, the range from 127mm to 150mm is

typical. Most of these lenses are 4 element designs, and capable

of producing reasonably decent photographs. They have lots of

coverage, and will often cover a 4x5" film. Stopping

down will minimize many aberrations of these less pricey lenses.

If you are on a beer budget and want to explore large format on the

ultra-cheap, these postcard folder camera lenses are the cheapest option

you can find that will cover the 4x5" format.

You don't have a lot of shutter speed options on most models either. This

factor means you need to pick your film speed with the expected lighting

and desired f/stops and available shutter speeds in mind. But while the

range is limited, the cameras were widely used under varying conditions,

and will probably yield good results with careful and thoughtful

use.

If you elect to try and light

a panoramic shot with our very wide lens options, you may need this

information. Flashbulbs are available (see Bill Cress

and Irish Megaflash corp and other links under

flashbulbs).

While there are some 135mm telephoto lenses for panoramic camera users,

they aren't nearly as popular as the wider and very-wide angle lenses.

Such lenses range from ultrawide 47mm super angulons (as on my Brooks

Veriwide 100, an 18mm equivalent on 35mm) to very wide 65mm and 75mm wide

angles on up to 90mm superangulons.

When used on the 6x17cm cameras, the

90mm super angulon or extended coverage 90mm XL super angulon has to be

used. Even then, a very pricey ($300+ to $700+) center filter is often

needed to prevent dark corners or vignetting when shooting flat lighted

subjects like the sky.

So I was surprised to see article by noted photo author Roger Hicks in the

British Journal of Photography of January 15, 1997 titled

Longfellow 6x17. The Longfellow 6x17cm (or 6x18cm) camera was made

by cutting and gluing two identical 6x6cm cameras (Ensigns) together with

epoxy and screws, nuts, and bolts. No, I am not making this up. If you

want a long camera, the easiest way (other than my way above) is to cut

and paste two short cameras together! Now add a 90mm Angulon f/6.8 lens.

You may have noticed that I didn't say 90mm f/6.8 "super" angulon above,

which is a lot more pricey lens with better coverage. The newer XL version

of the 90mm f/6.8 super angulon is used in some 6x17cm panoramics,

although the Fuji 90mm lens reportedly has even better light falloff. But

using an older 90mm f/6.8 angulon is possible because we only need 156mm

of lens coverage on a fixed non-shifting 6x17cm panoramic camera. The

older $250-350 US 90mm f/6.8 angulons can (barely) provide this, so there

isn't much need to spend more on your homebrew Longfellow 6x17cm or 6x18cm

camera.

If a 90mm f/6.8 lens can cover 156mm on a 6x17cm camera, it can certainly

cover 130mm or 6x14cm on our Postcard Panoramic Camera. The lens focal

length is also closer to the standard lens (typically 121-127mm or so).

This factor will make it easier to mount without having to get into wider

bellows (e.g., with 47mm and 65mmm and 75mm lenses). But you will have to

worry about projecting bellows cover getting in the image in some cases.

If you elect to try the more expensive and wider lenses, you will probably

end up replacing the bellows and

permanently modifying the case.

But recall my points on the limited degree of enlargement to be expected

by the typical amateur photographer user. Most of us will only get 4.5X

enlargements onto 24 by 10 inch print sizes. Lots of times, you will only

be looking at the original 55x130mm film itself on a lightbox, or making

contact prints. So you may not be getting all the benefit out of those

kilo-buck very wide 5x7" coverage lenses.

For those few times when you really need a top of the line image for a

commercial client, consider renting one (and tax

deducting the whole deal). Otherwise, you may end up with a $17,000+

investment in a panoramic 6x17cm camera and wider lenses that you only use

too infrequently to justify buying.

The advantage of wide and ultrawide lens mount adapters is that they are

very cheap, especially compared to the lenses they mimic or replace. I

have purchased both 0.6X and 0.42X adapters for under $25 US (in 1999 and

2000) from camera dealers and on EBAY. So if you try this approach and

don't like it, you can always resell these optics with little or no money

losses.

The 0.6x lens converts your normal lens into a wide angle lens roughly

equivalent to a 30mm on a 35mm SLR system. Simply multiply the adapter

factor (0.6X) times the normal lens focal length (50mm lens on 35mm SLR)

to get the equivalent wide angle lens (here, 30mm). For a 0.42X adapter,

you end up with a very wide 21mm lens equivalent on a 35mm SLR. That

transformation is a pretty big one for the small $25 US or so cost of the

adapter.

Using these same adapters on a #122 camera lens of 127mm focal length,

covering 3 1/4" x 5 1/2" (or circa 4x5"), is much more impressive in terms

of financial and optical gains. Using the recommended 0.6X adapter on a

127mm lens converts it to seeing the equivalent of a 76mm lens -

effectively the field of view of the popular 75mm view camera lenses. The

0.42X adapter drops you to 53mm ultrawide for a large format

(4x5") equivalent lens.

There is also a modest expense ($25) 0.5X adapter,

not as extreme or as distorted as the 0.42x ultrawide adapter, but wider

than the 0.6X. This adapter used with the 127mm normal lens will yield

about a 63mm equivalent optic field

of view, very close to the popular and very pricey, very wide view camera

optics. So you have a wide range of adapter choices worth experimenting

upon to see the effects they produce.

You may also see a more expensive true fisheye adapter (180 degree

adapter). This device produces a circular fisheye image on film. While it

might have some unusual applications in our panoramic cameras, it is

expensive ($50-100+) and has greatly reduced coverage in the central

region only of most lenses. You do get the circular (not

rectilinear) fisheye effect. With the

standard lens, you will likely get a modest sized circle of fisheye

effects, but not coverage to the edges. I mention it simply because you

may have one and want to experiment with it, or may be looking for a new

effect to try with panoramic photography. Or you may need a larger image

circle from your fisheye lens than your 35mm or standard 645 to

6x7cm medium format camera can

deliver.

The bad news is that these lens mount adapters are not as good as prime

lenses in resolution, aberrations, and resistance to flare. Fortunately for us, the lower resolution

effects are minimized thanks to the low degree of enlarging. When you try

such an adapter on a 35mm SLR, and view the slide or enlarge to 5x7 inches

or 8x10 inches, you may be disappointed. The same adapter on medium format

is enlarged less to similar image sizes, and the results are more

acceptable. Now enlarge even less thanks to the panoramic approach (e.g.,

no enlargement at all in the contact prints, 4.5X enlargements for

affordable 10" x 24" prints).

While the ultrawide 0.42X adapter provides the widest angle of view, it is

not a rectilinear wide angle. You will see some considerable wide angle or

barrel distortion, especially in the edges, and maybe even some

vignetting. The 0.6X adapter is less extreme, and a better behaved and

less vignetting wide angle. You may also want to know that there are new

designs of these adapters for video camera users who need wide angle

effects. These adapters are smaller than the older heavier glass models,

and may work as well with this application.

Please notice that these adapters fit in front of your regular camera

lens, just as if they were a filter. If your lens doesn't have a filter

mounting ring, you will have to rig one up. The easiest way is to find a

slip-on filter ring to match your lens, such as was used by owners in the

past (often series IV, V..). You may be able to find such an item at

camera shows, from the Filter Connection or other speciality filter shop

sellers, or from dealers online. I cheat. I find

a standard filter that fits in front of the lens without vignetting. Then

I bust out the glass, carefully, and epoxy or glue the glass-less metal

filter ring in place. Now I can screw in any matching filter thread

size filter or step-up adapter into this metal filter ring. Instant

adapter for minimum fuss and low bucks. Now I add a step-up ring to

Series VII so I can

mount these 0.6X and 0.42X adapters. I can also mount any filter I

need and have, if I have the right step-up ring or adapter.

Incidentally, you can put a mark or notch on a polarizer filter, and then

hold it notch up and rotate the filter until you get the desired effect.

Now you can mount the filter, again with the notch up, onto the camera

while keeping it aligned as before. The camera should see the same degree

and kind of polarizer filter effect as if it were on an SLR. Some filters

have these marks and degree setting rings on their rims already, for

rangefinder camera users. They also work well in the standard panoramic

camera setup if you are using the normal or standard lens alone

(46-54 degree coverage).

Be aware that with very wide angle and even wide angle shots, the

polarizer will cause its own darkening variation effects, often quite

noticeably so in the blue sky areas and other evenly lighted areas. So

while polarizers can be used with the standard lens setup cameras, they

are less useful with some wider angle lenses.

Another useful accessory is the wire frame sportsfinder. This device is

just what it sounds like, an open wire frame that mounts on the top of the

camera. You line up a bar with the center of the frame ( [+] ). Now simply

bend the wire so you see what the camera sees. How can you tell what that

is? Simply open the back of the camera, as if you were loading film. Trip

the shutter on Time (T) or (bulb (B) with a locking cable release). Now

you can put a piece of ground glass (from a glass/mirror store) where the

film would be. Focus. What you see on the glass is what the film will see

when shooting. Simply bend the wire frames to match when your eye is lined

up properly.

A deluxe aiming device such as the Leica optical accessory viewfinder for

the ultrawide angle setup (21mm) is unfortunately expensive - four or five

times the cost of the rest of the camera! You will find some lower cost

Russian viewfinders on the market. As a scuba diver, I have used a very

larger Ikelite viewfinder for underwater cameras in housings with various

masks marked for different lens angles. These finders cost around $100,

but they are bright orange in color to be easier to find underwater and

quite large (size of a lemon) to be easier to see in a diving mask.

You can also build one using tips on our fisheye

pages and a door "peepsite" which is a very wide and cheap ($10-12 US)

very wide angle fisheye finder. A bit of yellowish clear plastic from a

plastic report cover (for college papers) can be cut out to mark the lens

areas too. Yellow is easier to see, being higher contrast to the

eye.

I have also made rectilinear ultrawide bright accessory finders out of the

optics from discarded Texas Instruments DLP Digital Light Processor

wide screen TV projectors (topcon optics). While these surplus optics just

cover a DLP chip, they work nicely with an eyepiece as a bright large (1

1/2") finder. Some looking around may turn up similar optical

options in surplus optics stores in your area too?

The most common problem in older bellows mounted folder cameras is

pinholes in the bellows. See our bellows

repair pages for trips on using some black rubber adhesives to fix

this common problem. See also our Bellows Repair and Replacement Pages

for related repair tips and notes too.

Considering many of these lenses and leaf shutters are much older than I

am, they are often in better shape. The Kodak ball bearing leaf shutters

are simple and often surprisingly robust after decades of storage. The

lenses are often simple, although a few of the Kodak #3A special models

had Bausch and Lomb and other higher end optics.

Similarly, some models sport viewfinders, others add wedge prism finders,

and a few such as the Auto Kodak Special #3A featured a coupled

rangefinder while using #122 film delivering the familiar postcard sized

images. In other words, it may be worthwhile to consult McKeown's Classic

Camera Price Guide and other references in a library to learn more about

postcard sized cameras and #122 rollfilm models.

If you plan on mainly using the camera with a wide angle adapter, the

depth of field and changed optics will negate the benefits of a

rangefinder (and some models of the Auto Kodak Special didn't have the

coupled rangefinder either, so beware!). I have looked for cameras with

rollfilm formats that are low cost and common enough to be easily found

and converted, and nothing seems to beat the #122 rollfilm Kodak #3A

series so far. But if you have or find any candidates for better

conversion, please Email me

with the model and details. Thanks!

You may have some unusual need to shoot 220 rollfilm, or even 70mm film,

to get a particular emulsion or use stock you have. Since the Postcard

Panoramic Camera film

channel is 3 1/4" wide, you can physically fit 220 rollfilm just as well

as 120 film. However, you have a risk of scratches to the back of the film

where the protective paper runs out over your images. Possibly a film

paper thickness sheet placed on the film plate area will both protect and

adjust for any film paper thickness issues.

Similarly, you probably aren't going to be able to use the standard 70mm

film cassettes for obvious reasons. But you may be able to use 70mm film

stock in the camera by darkroom loading and unloading (or use a changing

bag).

In short, while you could physically fit and use the 220 and 70mm

rollfilms, it would seem to be easier to just use the same emulsions in

120 rollfilms. Still, lots of panoramic cameras can only use 120 rollfilm

physically. So if there is some reason you need either 220 or 70mm film

stocks, the potential to use them in these larger film channel cameras is

there.

But if you could nibble just a half-inch from either side of the film

channel, your 6x14cm Postcard Panoramic Camera would become a 6x17cm

Postcard X-Panoramic Camera! So if you really, really need the wider

standard format, or really, really can't stand wasting any film, this

project might be worth looking into.

The better "least resistance" approach is to look into a rotating

panoramic camera. You need one regulated voltage DC motor to control the

film advance speed, and a second regulated voltage DC motor to rotate the

entire camera around. These rotary cameras use vertical slits 1 or 2

millimeters wide as a shutter (with the lens shutter to Time exposure

during use). A rotary camera is actually rotated around the lens node rather than the center of the

camera.

One piece of good news is that you don't need a particularly expensive or

wide angle lens, except to get the desired vertical angle coverage (e.g.,

typically 28mm and up equivalent on 35mm SLR). You can use any medium

format camera that you can wind film with. The older Kodak and other

folders let you wind film without any stopping mechanism (except seeing

the number come up in the red window at the back of the camera). So they

might be ideal for such a conversion. A tripod, battery, and a few motors

and parts from Radio Shack would be the bulk of your other costs - plus

test film!

When thinking about candidates for conversion, keep in mind the benefits

of that film shifting technique I have described above. This shifting

ability is just as valuable in a rotating panoramic camera as it is in a

fixed one. The film advance on these old cameras is very simple, and

easily adapted (epoxied) to a regulated voltage DC "motor drive". The

folder camera is also lightweight, making it easy to mount on a small

motor on a tripod for 360 degree (or less) rotations. With the 0.6x or

0.5X lens mount adapters, you can even expand the vertical angle of

coverage of the standard lens. This trick simulates putting a wider angle

lens in place on the camera. In short, keep those low cost #3A (and #1A)

cameras in mind when looking at medium format rotating camera projects.

The potential advantage of film shifting is so great that it alone

would justify switching to this camera over other models, just to get the

great benefits of the film shifting effects.

The Nimslo 3D

panoramic camera idea of Andrew Davidhazy (of RIT Photography

Program..) shows how picking the right camera makes it easy to make a 72mm

long panoramic camera with the lens coverage of your choice. As with this

Postcard Panoramic Camera, the results are surprisingly handy, considering

the price is well under one percent (1%) of the cost of a similar

commercial panoramic camera (Fuji/Hasselblad X-pan at $2,000+).

I see lots of great cameras being machined and precisely ground and built

up. But most of us don't have the facilities or skills to do that kind of

work. The Postcard Panoramic Camera described here requires virtually no

tools and only a 120 film adapter to turn it into a panoramic camera. With

a few tricks, we can coax a surprisingly effective range of shifts out of

the camera too, thanks to my film shifting technique described

above.

good points re: shifting; my 6x14cm design uses "film shifting" instead

of lens shifting, which is an approach I haven't seen formally used on

any other panoramic camera designs - new to me, anyway ;-) ...

with film shifting, you can have a rigid camera body (or bellows too) and

build the film channel say 25mm or so _larger_ than the actual film size.

Now you put the film on an extension adapter so it moves horizontally at

any desired point in that +/- 13mm shift range (fixed shift adapters or

turn screw to desired shift point on variable adapter). Just be sure

film is horizontal at the shifted point! ;-)

The film "floats" up or down in the actual film channel, which is

equivalent to shifting the lens up or down a similar amount, or equiv. to

cropping a larger film size at that shift offset. You can keep the camera

horizontal on a level tripod, but setup a film shift of +12mm, thereby

minimizing converging verticals etc. by moving the film down into the

lower (or upper) section of the lens coverage. Again, same as shifting

the lens, but easier and lots cheaper to do with a rigid camera body, if

the lens has the coverage as you noted...

the "gotcha" is that you have to select a film shift when loading the

film, based on anticipated shift needs (in buildings or monument subjects)

or leave centered (for vertical shots or no shifts needed). Seems a good

tradeoff, esp. if you shoot seconds of major shots and bracket ;-)

Closest comparable camera is one of the 6x12cm (Linhof) which has a

permanent 8mm shift reportedly built into the camera, which can't be

removed, making it an issue for vertical shots and a middling shift amount

for times when you really need/want the full 12mm or more shift many

panoramics offer. Film shifting provides the same built-in shift effect,

but it is variable, and the lens is left centered on the camera.

Naturally, you could shift the lens in a film shift camera (say 12mm) so

when the film is at the top of the channel, no shift is selected (e.g.,

for verticals..); but shift up to 25mm or the full width of the film

channel provided, as noted, the lens has enough coverage for such a

trick! ;-)

the film adapters/spacers are much simpler for a homebrew design than a

shift lens mount mechanism, more robust, and very cheap with the right

lens and starting camera body, and a rigid body rigid lens design is easy!

I'd be interested in any other camera designs which used this "film

shifting" approach, since it seems both obvious and useful for many

needs, but I have yet to see such an approach in any current panoramic

cameras in the materials/books I have available...

regards bobm

* Robert Monaghan POB752182 Dallas Tx 75275-2182 [email protected]

*

* Medium Format Cameras: http://www.smu.edu/~rmonagha/mf/index.html

megasite*

On Mon, 3 Apr 2000 [email protected] wrote:

> One of the nice things about the V-Pan is WYSIWYG: What you see is what you > get. There is nothing sacred about 6 x 17. If you look on the viewing > screen you may discover that the image circle is smaller than what you hoped > for, but the image works and you have only to do a little cropping. Chet > Hanchett himself suggested putting some little black boards on the sides of > the film magazine to crop to 6 x 12, and there's nothing sacred about 6 x 12, > either. And don't forget, the image circle thrown by the lens may just cover > the 6 x 17 format, but sometimes you want to shift the lens, and then the > bigger the image circle, the more room you have for shifts. Chet recommends > an image circle of 200 mm for full coverage of the V-Pan frame. There have > been times when shift was more important to me than frame size - so I just > shifted the lens, and later cropped the edges straight. > > Liz Hymans > > In a message dated 4/3/00 4:27:31 PM Pacific Daylight Time, > [email protected] writes: > > As soon as I find a mm ruler I'll send you specs for my > V-Pan mark III. Do you want the film gate diagonal as well. You of > course are aware that published specs for image circles are often > conservative. And are talking about the older 90 mm f/6.8 Angulon or the > current or original version of 90 mm f/6.8 Super Angulon? Three > different lenses with different specs.

Date: Mon, 10 Apr 2000

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.large-format

From: [email protected] (Mr. Wratten)

Subject: Re: Inexpensive, homebrew 6x17 panoramic?

[email protected] (Becca Stephens) wrote:

>Is it possible to inexpensively use an old Speed Graphic with a rollfilm >back to make an inexpensive panoramic camera? Or would a 6x18 rollfilm >back be too expensive or impossible to find? > >Or should I just consider buying one of those cheap Russian Horizon pan >cameras?

Judging from the other posts, you want to shoot rollfilm in a larger

format than is normally available (6x9). You discuss using a Speed

Graphic, which can only shoot up to 4x5 in, or 10x12 cm. You say you

don't want to use sheet film. So, here are my suggestions:

1. Find a good 112 roll film Kodak from a long time ago (5x7 film format)

and modify the camera to take 120 roll film (not too hard, but cameras are

very old).

2. Find a good 122 roll film camera (3.25 x 5.25 film format). A Kodak

3A, for example. Modify to take 120 roll film. Again, cameras are very

old. May have problems such as leaky bellows, etc.

3. Find a good Polaroid roll-film camera (model 150, 800, 900), modify to

take 120 roll film. A slightly more involved modification, but only

slightly.

Film format is about 3.25x4.25. You also get rangefinder focus with this

modification. Cameras are very cheap ($10 or so) and high quality, but

exposure system is rudimentary. You could also find a Pathfinder (110,

110A, or 110B) that has not been modified into a pack film camera (they

have "normal" lens/shutters as opposed to the Polaroid EV exposure

system). Buy a 110 as opposed to am A or B model, they are harder to

modify into pack-film cameras and are cheaper for that reason (usually

less that $100).

4. Find a good 116 or 616 roll film camera, modify to take 120 film. Film

format is 2.5x4.25. The easiest modification, discussed here:

[Ed. note: http://medfmt.8k.com/bronfilms.html is update of old link at

http://www.smu.edu/~rmonagha/bronfilms.html]

Good luck,

Jim

From Koni Omega Mailing List:

Date: Wed, 05 Jul 2000

From: "Martin F. Melhus" [email protected]

Subject: Re: [KOML] 58mm image circle - coverage for movements

johnstafford wrote:

> I have similar reservations regarding film flatness. Some people are > experimenting with the US Navy surplus "Torpedo Camera" back, but it seems a > hassle to adapt it to 220/120 spools.

Another approach that I've heard for cheap MF panaroma is to get one

of the really old folders that takes some big goofy film size that is

no longer made, make adaptors to hold 120 film, and put edge holders

or some sort of mask on.

The problems with this approach are:

1) Film flatness - manageable if you have the resources.

2) Hard to find cameras.

3) Old lenses are usually not so great, typically 2-3 element

uncoated.

But they are cheap.

Regards,

--

Martin F. Melhus

[email protected]

From Koni Omega Mailing List:

Date: Thu, 06 Jul 2000

From: Lyndon Fletcher [email protected]

Subject: Re: [KOML] 58mm image circle - coverage for movements

>Another approach that I've heard for cheap MF panaroma is to get one >of the really old folders that takes some big goofy film size that is >no longer made, make adaptors to hold 120 film, and put edge holders >or some sort of mask on.

I have heard that the Kodak 3A camera is the one you should go for, a very

very large negative area designed in the days when you needed big contact

prints,

>The problems with this approach are: >1) Film flatness - manageable if you have the resources. >2) Hard to find cameras.

They are incredibly easy to find. I have had a friend in the US buy 6 for

me on Ebay most I ever paid was $30 with between $12 and $20 being

typical.

He is saving me the bodies of 2 of them, I actually bought the camera for

their lenses.

>3) Old lenses are usually not so great, typically 2-3 element > uncoated.

Most of them are Cellor type 4 element airspaced lenses of around

130-170mm and f7.7, very nice LF lenses if a little slow. They are the

best LF lenses you can get for under $50. FYI the Kodak 203mm Anastigmat

used on the Speed Graphic is one of these types of lenses. With coatings

it became the famous 203mm Ektar. Nothing wrong with a lot of the lenses.

The later cameras with the faster f6.3 lenses are mainly triplets except

the "Specials" which are B&L made Tessars.

Anyway, that is accademic, you would HAVE to change the lens for something

wider anyway to make a better Pano picture. I have been told that the 90mm

Angulon (not SA) has the right coverage and price for this kinds project.

These cameras have a flat bead and unit focussing meaning that any lens

can be used if infinity stops and focus scales are changed.

Lyndon

...

From KO Mailing List:

Date: Thu, 06 Jul 2000

From: Clive Warren [email protected]

Subject: Re: [KOML] 58mm image circle - coverage for movements

....

Hello Lyndon,

Have you tried the Kodak 3A Cellor lenses yet? Would be interesting to

know if they were colour corrected......... it seems unlikely.

The 90mm Angulon struggles to cover 4x5 - you need to stop it down to f32

(hence the name of one of my web sites - www.f32.net). Diffraction

problems then start to degrade the image resolution and contrast. At f32

you can get a half decent trannie. So, it may be OK for landscapes with

slow film but it's pushing the boundaries and doesn't give a whole lot of

flexibility.

Have been trying to contact you for a while now to say thanks but mail has

always bounced back - please EMail me off list at CoCam.

All the best,

Clive http://www.cocam.co.uk

From KO Mailing List:

Date: Thu, 06 Jul 2000

From: "Martin F. Melhus" [email protected]

Subject: Re: [KOML] 58mm image circle - coverage for movements

Clive Warren wrote:

> At 11:47 pm -0500 5/7/00, Martin F. Melhus wrote: > > >Another approach that I've heard for cheap MF panaroma is to get one > >of the really old folders that takes some big goofy film size that is > >no longer made, make adaptors to hold 120 film, and put edge holders > >or some sort of mask on. > > You can find a good selection of 6x9 folders this way, 6x12 is also a > possibility.

Actually, the ones that I'm talking about predate 120 film by a lot.

I have three 6x9's and they are very nice (esp. my Voigtlander

Bessa I with a 105mm 4 element coated Scopar lens.) But they aren't

really panoramic, in that they have the same aspect ratio as a standard

35mm camera (3:2).

I'm talking about the real antiques, from 1910-1939 or so. These

cameras take film that is perhaps 4 inches wide and take shots

that are between 8 and 12 inches long. You use most of the length

and just as much width as a roll of 12 film will allow. This allows

you to mostly use the center of the lens, where distortions are at a

minimum.

The conversion to 120 film is not so difficult from the roller end.

Just use wood and glue to build an adaptor that will hold a MF roll

securely. Getting the film to stay flat is the real trick. If I

knew how to do that well, I'd own several of these cameras. If I

ever figure it out, I'll post the results somewhere appropriate.

Sorry about the off topic posts.

Regards,

--

Martin F. Melhus

[email protected]

Date: 14 Nov 2000

From: Martin Jangowski [email protected]

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.large-format

Subject: Re: Angulon 90 f/6.8 - what hole?

Victor Bazarov [email protected] wrote:

> About to get the Schneider-Kreuznach 90 mm f/6.8 in Synchro- > Compur. Could anyone please tell me what diameter of the > hole in the lensboard is needed?

The Angulon 6.8/90 should be in a #0 shutter, you'll need a 34.6mm

hole in your lensboard.

Martin

From Bronica Mailing List;

Date: Thu, 14 Dec 2000

From: Kelvin Lee [email protected]

Subject: Re: [BRONICA] Metered prism finders for S2A?

http://www.craigcamera.com/access.htm

I think you may have this listed already, but this guy sells replacement

bellows for old KOdak cameras like the 1a and the 3 from US$10. Great for

restoration.

[Ed. note: some shift can be handy; see Medium

Format Shift Lenses Pages for more info...]

From Rollei Mailing LIst:

Date: Mon, 18 Dec 2000

From: Andy Buck [email protected]

Subject: Re: Noblex cameras

I've used the 150 with shift & focus and agree about

the shift: it's so little it's hardly worth it (and

why I had a 5" 360 w/1" shift made). also, 150 vs 175

is odd because the 175 actually has a narrower angle

of view: 138 degrees horizontally vs 146 degrees with

the 150, and obviously less vertically, since it's a

75mm lens vs 50mm with the 150. btw, the names are

deceiving, too, since the negative on the 150 is

50mmx120mm and the 175 is 50mmx170mm.

only other comment is that the lens (on the 150) is

one of the sharpest I've ever seen and, I've heard,

the sharpest currently availble on any camera and

possibly made by zeiss.

a

From Panoramic Mailing List;

Date: Mon, 18 Dec 2000

From: Ellis Vener [email protected]

Subject: Re: Noblex cameras

>I've used the 150 with shift & focus and agree about >the shift: it's so little it's hardly worth it

While this may be true with landscape work where everything is pretty

much at infinity, for interior work the shift is very handy and very

much worthwhile having, likewise for landscape and cityscape

compositions with a dramatic near/far composition.

Ellis Vener

[Ed. note: another idea using 70mm stock film...]

From Panoramic Mailing List;

Date: Thu, 14 Jun 2001

From: Lyndon Fletcher [email protected]

Subject: Re: starting with a Kodak pocket

>Lyndon > >It is a number 1A pocket, >bellows, folding bed type, on the back it says "use film no 1116" > >The active part of the negative is about 4.25 inches 11cm long and 2.5inches >6.5cm wide.

Then this camera is not for 120 film but for 116. This is a (VERY) old

and discontinued film size, Kodak switched from this to 616 in the

early 1930's and 616 itself was discontinued I think in the early

1980's. Part of the reason I am always looking for unperforated 70mm

film stock is so that I can use some of the 616 cameras I own.

The first step is to adapt the camera to use 120 film. You will need

to reduce the size of the gate a little and put spacers bellow the 120

film spools. Marty Magid at [email protected] used to sell little

adapter kits for doing this if you don't want to do the job yourself.

Three things to remember. First, there are no markings on the 120

paper for an 11 inch wide image. This means that you will have to work

out a winding system. Using the 6x6 markings and winding on 2 frames

for every shot should work.. Remember also that the start point for

the film will be in a different position relative to the red window so

it would probably be wise to waste a roll of film working out the

start position of the film. Second, remember when you work out your

gate adaptations to position the film so that you can still see the

6x6 film markings though the red window. If this isn't possible you

will need to move the window. Finally, modern films are far more

sensitive to red light than their predecessors. Cover the red window

with black electrician's tape when not winding film.

>can I get a widerangle lens for this camera ? i

I have never done it with this type of camera and so a lot of this

information is based on reported conversions of 3a cameras (these have

bigger negative areas and this has effected the choice of lens.)

You will need a 90mm WA Optar, WA Raptar or a 90mm Angulon. A 65mm

Super Angulon way cover 6x11 (advice anyone?) and would give a much

more pronounced wide angle effect. Replacing the lens should be

relatively trivial. Most shutters are mounted from the back of the

camera with a locking ring. To remove it you will need to open the

back of the camera and unscrew the ring that holds the lens in place

with an optical spanner. Depending on the width of the throat on the

new shutter you may need to extend the hole diameter or use a small

reducer board to fit the new lens to the front standard. Make sure the

resulting joints are light tight.

To focus on closer objects I assume that you turn a knob on the bed of

the camera that extends the tracks and moves the standard forwards?

Some cheaper Kodak cameras of this period have 3 sets of stops one for

infinity, one for groups and one for close-up rather than allowing

continuous focus. If your camera is of this type and you are satisfied

with this limitation then follow this procedure for each focussing

distance. For the moment I will assume that the camera has a focussing

knob and one set of stops.

When you pull the front standard down it's track it locks in place at

a certain position. The distance from the lens to the filmplane at

this point will be the focal length of the lens. With the lens in this

position objects at infinity will be in sharp focus.

Wider lenses will have a shorter focal length than the one on your

camera. To be able to focus the new lens at infinity you will have to

move the position of the infinity stops backwards until the new film

to standard distance is the same as the focal length of the new lens.

First erect the camera as it would have been with the old lens. There

is usually a small vernier style focusing scale next to the track on

the camera. Set this to infinity.

Next open the back of the camera and stick some frosted tape tightly

across the film gate. Mount the camera on a tripod looking though a

window at a distant object. Cover with a darkcloth or thick coat and

open the shutter using the T setting or a locking cable release and

the shutter set on "B". Open the lens to it's widest apperture.

Keeping the position of the focussing scale at infinity release the

lens from the infinity stop and move it backwards, carefully checking

the focus of the distant object on the frosted tape with a loupe. When

the distant object is sharply in focus, mark the new standard position

on the movable track with a fine point technical pen.

You will now need to devise a method of locking the standard to the

movable rail at this new position. Depending on how it is constructed

it may be possible to move the existing infinity lock to this position

or just file an extra grove in a guide rail. In any case for a

focusing camera you need a method of locking the standard to the

movable rails at this point while still allowing the rails to move

easily.

Now measure out a number of known distances and place target objects

at these positions. Focus until the objects are sharp and record the

distances on the movable half of the camera's focusing scale. Using

this as a guide a new scale can be made and glued in place to replace

the scale from the old lens. If you have the 3 focal distance style

camera then just adjust the 2 other sets of focus stops for usable

distances.

>is it worth the effort?

If the camera is in good condition, if your adaptations hold the film

flat and you set the infinity focus correctly then the camera should

produce results as good as any other camera with the same lens. The

resulting camera should be fairly portable and give a wide field of

view.

Lyndon

From: David Littlewood <[email protected]>

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.medium-format

Subject: Re: shifting film trick, eccentric lens mounts Re: postcard panoramic

Date: Mon, 20 Aug 2001

Robert Monaghan

<[email protected]> writes

>

>

>another fun discovery is eccentric lens board mounts, with the lenses

>purposely mounted waaay off-center, so you have the desired shift (switch

>lens around in square 3x3 or 4x4" holder to vary vertical or horiz etc.)

>The linhof 612 already does this 10mm or so shift, IIRC, which screws it

>up for unshifted or foreground dominant work, but this isn't a new trick;

>however, it is the obvious way to get a low cost shift lens for the price

>of a spare lens board and mounting tool ;-)

>

Now this is interesting; the problem is that many wides require sunken

lens boards, which rather precludes the use of eccentric mounting. With

a drop-bed camera the upward offset would not matter as you could drop

the board below horizontal to take non-shifted pictures.

Hmm, this could be the solution to my limited rise problem with a 75 mm

on Linhof Technika IV. Where can I fine an offset sunken Linhof lens board? Could be quite a hairy machining job.

But this is rather the wrong NG, I guess.

--

David Littlewood

From: Struan Gray [email protected]>

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.medium-format

Subject: Re: postcard panoramic - features shift option, costs $50, 6x12/6x14cm

Date: 27 Aug 2001

Robert Monaghan, [email protected] writes:

> By swapping out adapters (which can be as simple as

> some nickels glued together), you can position the

> film up or down in the rollfilm channel, effectively

> creating a shift lens camera for cityscapes.

If you want a cheap shifting back with excellent mechanical

integrity you might want to look for older oscilloscope cameras.

These often had a polaroid back which could be shifted +/- 2.5

inches which allowed you to record several traces on the same

piece of film.

Struan

rec.photo.equipment.medium-format

From: [email protected] (JCPERE)

[1] Re: Wide-angle folder

Date: Fri May 17 2002

>Hi John - sounds like an interesting and fun project - but sadly, there

>just don't seem to be a lot of modest cost wide angle lenses to match

>the costs of most folders to make this a really attractive project to me?

Maybe a tiny 65mm Angulon would make a good folder wide angle. Covers 6x9 with

no problems.

Chuck

From: John Stafford [email protected]

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.medium-format

Subject: Wide-angle folder

Date: Thu, 16 May 2002

If you don't mind venturing into hand-builts, it's feasible to mate a 47mm

Super Angulon to an early folder such as the Ikomat 6x6 or 6x9. I've seen it

done. Maybe I'll do one this winter.

From: "Lyle Gordon" [email protected]

Newsgroups: rec.photo.equipment.medium-format

Subject: Re: 616 kodak film in old junior six-16...

Date: Wed, 25 Dec 2002

I did this with the senior version of your camera I place a motherboard

standoff (computer building screw-like thingy) on top and below the spool of

620 (120 didnt fit) film with a spool of 616 for the take-up. With this set

up I was able to take 5 pictures on a roll. Here is a link to one of the

photos:

http://members.rogers.com/lgordon/house.jpg (my house)

it produced interesting 6x12 panoramic negatives.

I would be willing to send you the 616 take-up spool and modified

motherboard standoffs if you are will to pay postage from canada.

My e-mail is [email protected]

-Lyle Gordon

"Andrea" [email protected] wrote

> Merry Xmas!

>

> Hi all, somebody gave me as a present an old folding camera. It's a Kodak

> Junior Six-16 series III, with a kodak anastigmat lens 126mm...

>

> I made a search on the net and i found out the following info:

> it was made 1938-39

> its negative size is 6.5x11cm (i think 2.5x4.5")

> film format is Kodak 616

>

> since i'd like to see this camera working (shutter seems to work pretty good

> and lens is acceptably clean for its age), i made i search for that type of

> film and i found out production has been discontinued since about 50

> years... :)

> but since the film which is supposed to go into it is just 1/2 cm taller

> than a typical 120 film (6cm tall), i was thinking that using a simple